Discover more from Michael's Musings

Ten years ago, a small, provincial television channel in Canada (TVO) invited me — a graduate student at the time — onto their flagship political show to discuss the ideas of Alexander Dugin. The co-translator of Dugin’s first book published in English, The Fourth Political Theory (2012), I was there as a subject matter expert who could help a Western audience better understand the Russian mind. Why did they want to know about Dugin and Russia at all? Think back to 2014. Putin had invaded Ukraine with little green men to annex territory, seeing post-Maidan Ukraine as a dangerous anti-Russian military outpost. In this milieu, Dugin had come to the forefront as the intellectual responsible for Putin’s illiberal geopolitics. That was the year Foreign Affairs famously dubbed Dugin “Putin’s Brain.”

Ten years later, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has only intensified, entering a new phase after Putin’s 2022 invasion. As I write this, Dugin is has just discussed geopolitics with the famous American foreign policy analyst and international relations theorist John Mearsheimer. A pro-Russian government has come to power in Romania. President-elect Trump is publicly threatening BRICS over its plans for economic and political multipolarity. And Tucker Carlson has announced he’s in Russia to interview Foreign Minister Lavrov. In short, Putin and Russia remain in the news and in our imaginations, as the world inches closer than ever to the threat of nuclear confrontation. Throughout this time, Dugin’s relevance has only grown.

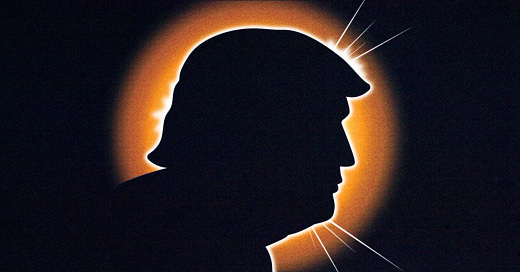

All these events, topped by the recent re-election of Donald Trump, have had figures like Fukuyama himself once again questioning the liberal “end of history” thesis. But perhaps it is finally time to recognize that during the last ten years we’ve not seen the end of history. We’ve seen the Dugin decade.

*

I have written so much about Dugin in the last ten years, and have given so many interviews about him (besides having interviewed him several times), that I can hardly bring myself here to provide another comprehensive recap of his worldview. But I owe you a brief word on the substance of the Dugin decade.

While the end of history thesis had argued that the world was tending towards global liberal unipolarity, Dugin was predicting, and calling for, multipolarity. As he wrote in his Theory of a Multipolar World and elsewhere, multipolarity means a world in which there are many civilizational blocs, not just a single model of civilization (indeed, in this respect Dugin’s view is closer to that of the Colombian aphorist Nicolás Gómez Dávila, one of whose aphorisms runs as follows: “Civilizations differ radically among themselves. From civilization to civilization, however, the few civilized men acknowledge each other with a discreet smile."

If this is all we ever learned from Dugin, it would still be valuable. Multipolarity has been one of the keywords of Putin’s reign, as I outlined in this Hillsdale presentation, and you would be better positioned to understand Russia’s actions on the world stage knowing that than you would be by forcing everything into the flattening perspective of global liberalism.

Another important element of Dugin’s thought — of course, he’s not the only person to have suggested this — is that liberalism represents to some extent a war on the human essence, or at least consists of an interpretation of what it is to be human that culminates in the technological overcoming of humanity itself. Dugin thus regularly supported reopening the question that, according to Thiel’s Straussian Moment essay had been closed off at the beginning of modernity and the enlightenment: the question concerning man. In pursuit of this question, Dugin studied, wrote about, and taught a wide range of pre- and post-modern authors, including mystics like Palamas, Eckhart, Suso and Tauler, as well as occultists and esotericists, like Paracelsus and Böhme. He wrote about “the sociology of the imagination” (Durand), and penned several books on Martin Heidegger, existentialism, and phenomenology, to say nothing of his most obscure yet important topic, that of the “Radical Subject.”

Do we find any recent evidence for the enduring relevance of such concerns? Consider the Joe Rogan podcast episode featuring Marc Andreessen as the guest. Andreessen says at one point that the medievals were better equipped to understand our world and its new technologies because the language of angels, demons, spirits and other divinities is conducive to interpreting non-human agents like AI. That is the kind of point Dugin has been making for over a decade.

These two topics — multipolarity and the war over what it is to be human — are linked, for Dugin. Geopolitical multipolarity, he has argued, reflects the multipolarity of nous, intellect itself. He wrote a series of books about that called Noomakhia, Wars of Nous. The model in that book series of three logoi, the Apollonian, the Dionysian, and the Cybelean, has also proven to be a valuable framework through which to view the gendered dimension of global politics. And the broader argument that geopolitical disputes can have something fundamentally metaphysical or philosophical about them has been buttressed by recent history, as the reaction to woke leftism run amok has sometimes taken the form of a traditional defence of human identity and the human soul. End of history theorists believed something similar about the relationship of philosophy and politics — the thesis is after all Hegelian — but for them the convergence of political and philosophical unipolarity was a good thing, though Fukuyama himself doubted that it would survive the vitalistic Nietzschean distaste for the last man, perhaps having learned from his teacher Leo Strauss that nature can be chased out with a pitchfork but nevertheless it returns.

I have tried over the last ten years to make the case that, despite whatever one may regard as his worst vices, eccentricities, and errors, Dugin deserves a place at the table among other, better known analysts of the shortcomings of liberalism like Deneen and Ahmari, as well as among first-rate political theorists and philosophers. He has written and said more than I have translated, studied, and discussed, but even the small number of works I have helped bring into English deserve our attention, works like The Fourth Political Theory, The Rise of the Fourth Political Theory, Ethnos and Society, Ethnosociology: The Foundations, Last War of the World Island: Geopolitics of Contemporary Russia, Political Platonism, and Theory of a Multipolar World.1

Other translators, too, have made his writings more readily accessible to an English-speaking audience. Consider, for instance, the slim 2021 booklet, The Great Awakening vs. The Great Reset. Written during the Biden administration, it lays out a plausible and compelling analysis of what was at stake in the decision between Biden (later Kamala) and Trump, and it helps us retrospectively to interpret the significance of Trump’s win. (My most watched interview, with almost half a million views, was a discussion of this book. I have also covered it here, here, and elsewhere).

We could go on and on with examples of the enduring relevance of Dugin’s analyses. Recent attempts to make “woke right” a thing, which in effect represent the classical liberal’s attempt to gatekeep against right-wing anti-liberalism, just remind us of basic points that Dugin made long ago: that there is something we can learn from leftist and even postmodern critics of liberalism, and that there is nothing centrist liberals won’t do or say to try to deprive their opponents on the left or right of any ground. Dugin, meanwhile, has allowed himself and encouraged others to engage in experimental thinking, for instance by creatively connecting Heideggerian philosophy and Islamic mysticism through the works of Henry Corbin, using the theses of Plato’s Parmenides about the One and the Many to map out the varieties of democracy, and analyzing “psychedelic Trumpism” through the lens of Lacan, something Zizek has taken issue with.

Dugin is not perfect. He’s not right about everything. He’s not above reproach. And there are good reasons why specific people and places might be extremely wary of him, in particular when they belong to communities that are coded as enemies by his political models. That is as natural in this case as in any other. People affected by communism are rightly wary of Marx, while those whose countries suffered under the influence of global liberalism may understandably not want to study liberalism’s greatest minds sympathetically. Some Jews are hesitant to read Nazi theorists, even when they are as significant as Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, both party members. So a degree of hostility towards Dugin is comprehensible. But I can tell you after a decade of receiving letters of thanks from people around the world that he stimulates thoughtful reflection in those who, although they may still be afraid to admit it publicly, listen to or read him privately.

Thoughtlessness, when it is not a deliberate meditative strategy or the result of a flow state, is a sin. So we should be grateful for anyone who awakens us from our slumber and pricks our minds into activity. That’s especially true when there are mighty forces working overtime on the opposite project of lulling us into a braindead stupor. And when our own ways of doing things and looking at them has led to a dead end, it can be stimulating to see the situation from an unfamiliar perspective, such as Dugin offers. There’s a reason why even those who do not agree with him fully have increasingly found him to be a provocative and insightful interlocutor.

*

My interview about Dugin greatly affected my personal and professional trajectory. It is one thing for a cute video of a child opening Christmas presents to “go viral.” But back then, at just about the time Jordan Peterson was rising in prominence, videos of academics lecturing on obscure topics were about as popular as most dissertations, which are read by their author, one or two committee members, and no one else.

But this interview was different.

Most people who talked about Dugin at all at that time did so as hostile liberal accusers. My goal, however, was to provide clear exposition of Dugin’s ideas, without any apriori hostility towards them. Indeed, as I said towards the end of the interview, I found aspects of Dugin’s criticisms of liberalism compelling, especially on the point that there is more to being human than being liberal. I had also learned from my work on Dugin that his interpretations of global affairs are perceptive and often predictive. The interview circulated among viewers who were surprised to find a comparatively neutral and at times even positive account of Dugin in the public media. A barrage of overwhelmingly favourable comments poured it (but have since been removed and comments turned off).

My academic environment, though, consisting entirely of liberals and leftists, did not react well to the interview. As I have discussed before (here, for example), I was accused of being a Kremlin stooge, an anti-semite, and all kinds of other things. My funding was attacked, my career path was sabotaged, and four professors resigned from my dissertation committee in a scandal that reflected badly on the profession. You have to remember that “the Putin question” did not only concern Ukraine. By 2016, America was facing the “Russia, Russia, Russia” hoax that accused Trump of working for the Russians. Trump derangement syndrome was in full swing. In the minds of the liberal and leftist professoriate, any “association” with Dugin was increasingly tantamount to unadulterated Russian Hitlerism.

With the benefit of hindsight, coming now towards the end of 2024, it is possible to look back on my interview and the academic scandal that ensued and to see clearly who were the winners and losers, who got what right and who got what wrong.

The liberal scaremongers have been left behind. They still see fascists around every corner. One wonders what they see when they look in the mirror. Whatever their academic accomplishments might be, their brains have been destroyed by politics over the past decade. They lack all ability to understand “Trump,” by which I mean not only Trump himself and his supporters in the United States but anyone anywhere who has good reason to doubt the unquestionable superiority of zealous liberal dogmatism to its alternatives. They supported the trend according to which everything normal was called fascist.

Amazingly, this is true even of that small subset that publicly prided itself on precisely the ability to understand and sympathize with the critics of liberal democracy. One such professor who resigned from my committee over Dugin, and who also went surreptitiously after my funding, and therefore, not incidentally, after my family, wrote an op-ed at the very time that he was sabotaging my attempts to reconstitute a dissertation committee, in which he argued that professors should always have the backs of their graduate students. Sorry to say, but if you ever looked up to academics, just spend some time near them. Soon you will run from them — to escape the stench. If you are lucky enough to find one who is a breath of fresh air, thank God for that. It’s a glitch in the matrix.

*

So there you have it. Ten years have passed since my first interview on Dugin. In that time, I’ve continued to work on the authors who help us understand ourselves and the world better, including Dugin and some of the authors he writes about, like Plato and Heidegger. Events over the last decade have only reinforced the importance of a basic familiarity with political theory, political philosophy. There’s a demonstrable hunger for meaning and guidance that not all modern, mainstream authors are able to satisfy. Accordingly, intelligent people turn to older sources, whether ancient or medieval, and to strange contemporaries, like Dugin, Yarvin, BAP, Land, and others.

And why not?

Those who ignored or suppressed these ideas out of what might have been a well intentioned desire to protect liberalism from its enemies often committed the grave error that Leo Strauss attributed to the progressive teachers who inadvertently pushed radical young German nihilists further away from moderation by proving to them the correctness of the students’ prejudices. What the students needed, Strauss wrote, were old fashioned teachers who understood the positive significance of their rebellion against bourgeois liberalism, to say nothing of socialism and communism. Old fashioned teachers understood that it is not Hitlerism to doubt that life’s alpha and omega is the production and consumption of material and spiritual values. Plato, Rousseau, Nietzsche and others all had their version of a teaching about man that took its bearings by another alpha and another omega, as does the religious right today. Should we not be permitted to consider these things and to discuss them?

Here’s the original 2014 interview, if you’d like to see it for yourself.

If you have learned something interesting from Dugin or my works on him in over the last ten years, or if you have anything else you’d like to say about the general topics I’ve raised here, I’d love for you to leave a comment. I see this anniversary as a time to celebrate the long, strange journey that has brought us here through a mutual commitment to education and understanding.

You can buy Dugin’s books from the publisher at https://arktos.com/book-author/alexander-dugin/ Use coupon code MILLERMAN for 10% off

Subscribe to Michael's Musings

Philosophy, education, politics, mysticism, and more.

Young MM is virtual and thus immortal…

One quintessential frustration with religion is that they won’t do as they preach. There is no opposition to globalism, corporatism, or the anti social offenses of liberalism. All of the ideas are very simple in philosophy.

Platonic, ‘tradition’, would say there are absolute forms, which is of a logical kind of thing. Good becomes evil and evil becomes good under the subordination of profit and monopoly. Religions have not sought justice, truth, or civilization, because they inherit broken forms from the current system. They always do. And they won’t listen when it’s pointed out, because they, as Zizek says, ‘defend their trash’.

There is a psychological weakness with religious bigotry and zealism. They neither value the forms very much, nor do they cite anything real about them.

Many kinds of anti capitalists exist who are at least trying to reveal the nature of things. The Capitalist hyper conservatives have not. Dugin an anti Communist. I would say I am a Marxist who reads Dugin.